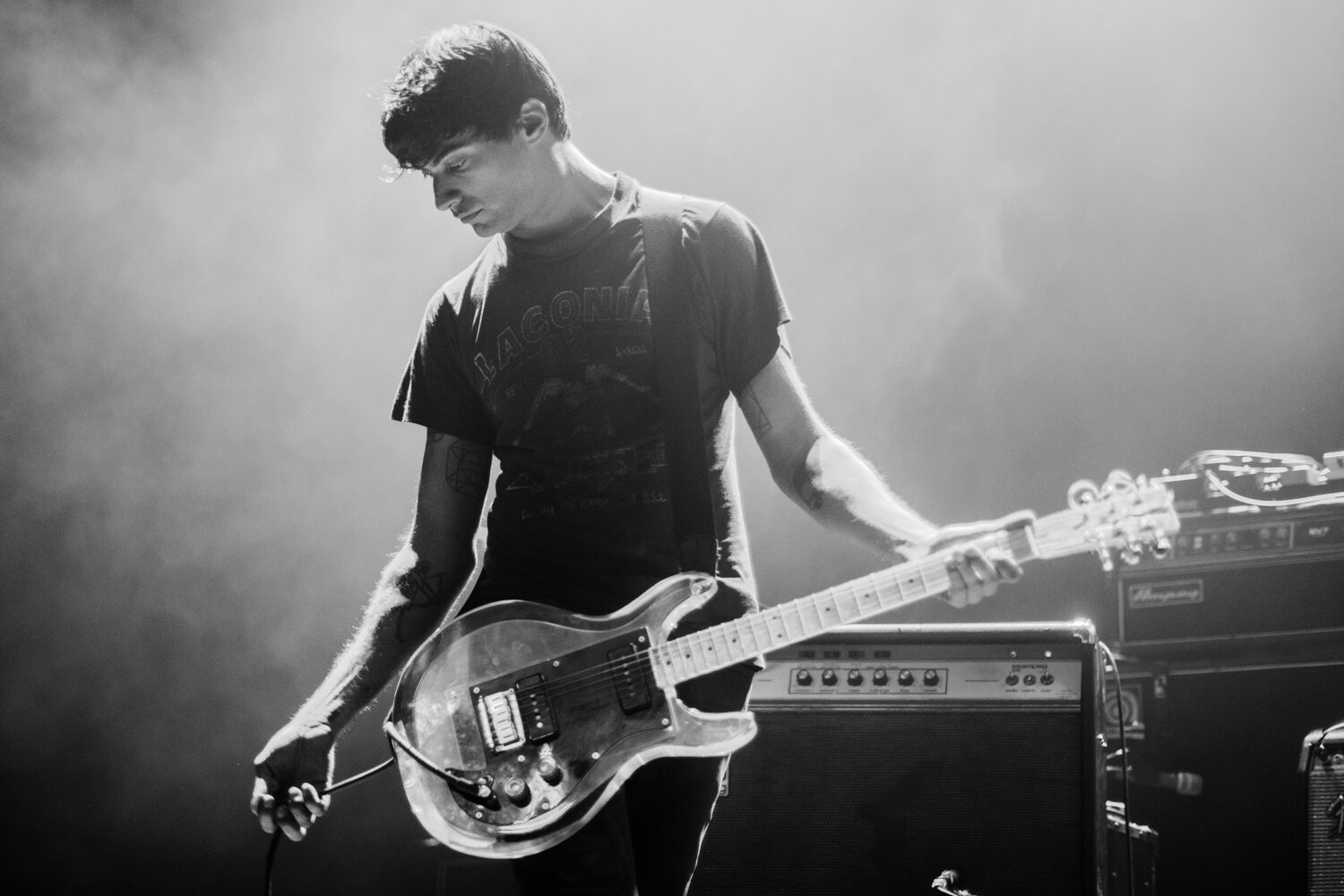

All pics by AF Cortes

I had wanted to have a conversation with Michael Berdan for a long time. Uniform is one of the most significant bands to me, which is probably why I hesitated to request an interview. You know the saying: never meet your heroes! We spoke shortly after the assassination attempt on Trump (and before Joe Biden withdrew from the presidential race), so I decided to start by asking about that. As he answered this one question for over 15 minutes, I kept glancing at the time, becoming more convinced that this would be one of the best interviews I would ever do.

[MOŻESZ PRZECZYTAĆ TEN WYWIAD PO POLSKU]

I need to start with this question: What the fuck is going on in the United States right now?!

Ha! I truly can’t even begin to quantify it, and it seems almost impossible to make sense of it all. I would imagine that Europeans might have more context for things like this, but as someone who grew up under late-stage capitalism—I was born at the end of the Jimmy Carter administration—I’ve lived through Reagan, Bush Sr., Clinton, Bush Jr., Obama, Trump, and now Biden. I’ve seen it all, and it’s just gotten weird. A lot of this weirdness can be attributed to the advent of social media, as well as shifting economic conditions. In particular, Democrats have increasingly shifted away from working-class politics, or even paying lip service to the working class. This shift has allowed the right to co-opt those talking points, which only adds to the strangeness of the current political climate.

Joe Biden is essentially a middle-of-the-road Democrat, albeit one who used more colorful language in his heyday. But that approach hasn’t worked, and it never really has. Then there’s Trump, who was initially seen as a joke—a real estate mogul turned reality star, turned Twitter loudmouth, turned whatever he is now. The period between Trump’s first term and Biden’s presidency has been pretty awful for a number of reasons. If you try to boil it down, not much has really changed under Biden. It’s the same deal as it was under Obama, Clinton, or any other recent Democratic president. They do the same things, but they’re just more polite about it. They’re better at lip service, better at keeping things quiet, and maintaining the status quo. All Trump did was make everything louder. Yes, there were terrible things that happened under Trump, particularly regarding immigration and the Supreme Court, but it all just sucks.

As a leftist, I find myself conflicted. Part of me thinks, „Whatever, Trump’s a chaos agent,” and maybe his presence could add fuel to a necessary fire that sparks real social change. The whole system needs to be destroyed before it can be rebuilt. But then again, we already had Trump, and that didn’t happen. We’re all hoping for a bloodless revolution, but revolutions are rarely bloodless, and the people who get hurt the most are usually those without institutional insulation and economic means. Biden’s presidency has afforded me some degree of quiet, and selfishly, as a white middle-class dude, I appreciate that quiet. But at the end of the day, when we talk about Democrats and women’s rights, for example, the Democrats will never codify Roe v. Wade. If they did, they couldn’t fundraise and fearmonger on the issue anymore. They’ll dangle that carrot forever, perpetually keeping it at risk because they don’t actually want it to be safe.

We’re screwed. I already thought Trump was going to win, and after the assassination attempt, he’s all but assured to win. I had already planned on writing in Cornel West, and I’m still going to do that. I can’t in good conscience support either major candidate. Trump will vocally support Netanyahu and the Israeli regime, and the bombing and displacement of hundreds of thousands of innocent indigenous people, while Biden will do the same thing, just more politely. At the end of the day, I have to draw the line at genocide. I don’t see things improving for the working class here, which has always been my primary concern. I don’t see America doing anything to stem the tide of racial injustice around the world. The crisis at the southern border, for example, is a direct result of the CIA’s actions in Latin America in the 1980s. The U.S. ruined these countries out of fear, trying to stem the tide of communism. Now, decades later, these countries are plagued by warlords and lack economic opportunities, so people are willing to risk their lives to come north.

What are we doing to improve the countries we waged shadow wars against decades ago? Nothing. There’s no infrastructure in place here to deal with it, but it’s still our responsibility. I don’t know what the answer is, but I do know that the problem stems from America, and I don’t see America doing much of anything to fix it on a larger scale. At the end of the day, I can only care so much. None of our choices are good, and none of them will allow me to sleep soundly. So, I’m going to do what I said and vote for someone who won’t win but whose politics align with my own. That’s all I can do.

It’s so weird; it feels like we’re watching a live stream from the end of the world. Every time I wake up, I think, „This is terrible, but it can’t get any worse,” and then it does. It’s a very strange world we live in, and the whole Trump situation sometimes feels like a joke, like it’s staged. I keep expecting someone to pop out and say, „You’ve been punked!” because it’s so hard to believe that this person, who seems so foolish, has garnered so much support.

I have to admit Trump puts in the groundwork. The shooting happened in a rural area outside of Pittsburgh, and his support largely comes from far suburbs to rural areas. He knows how to talk to and manipulate poor white people, and increasingly, poor people in general. He’s gaining support from within Hispanic and Black communities, too. Trump talks to poor people about money and infrastructure, and he uses the same tactics Hitler did by saying, „This isn’t your fault; it’s these other people’s fault.”

Democrats don’t know how to handle that. They operate from the top down. Take Hillary Clinton, for example—no wonder she lost. She barely visited the Rust Belt, while Trump was there constantly, spending six out of seven days a week connecting with people. Who’s going to carry the former coal towns? The candidate courting Manhattan elites or the one spending time in those towns telling people they’re the salt of the earth and pointing the finger at those supposedly responsible for their struggles?

Trump is a monster and a grifter, but his strategy is simple. It’s a tactic used throughout modern times: you tell the masses they are valuable, worth more than they’re getting, and then you point to a specific group or institution as the problem. People love a boogeyman. Democrats do this too, but I hate Trump, and I hate them both. I’m disappointed to my core with the state of American politics, now and throughout my lifetime. The last president I can read about and feel did anything altruistic for the world at large was Jimmy Carter, and I was only alive for four months of his administration. What can you do? We’ve created this mess.

Since you live in New York, a place known for its artistic influence and global impact, I’m curious about how the city has changed after the pandemic, especially in terms of its music scene and artistic culture.

It’s hard for me to put into words because these changes happened as I was aging out of a lot of the more social music scenes. I moved here shortly after 9/11, coming from Philadelphia. Back then, New York was still relatively affordable. You could move here, get a job that paid three times as much as what you’d earn elsewhere, and still make ends meet. There was a thriving art scene, a vibrant club scene, and a strong punk community. But over time, as rents went up and wages stayed the same, that dynamic shifted. The advantage of earning more in New York gradually disappeared, and many people who were committed to the cultural landscape either had to move out or aged out. With that shift, there are fewer bands, fewer shows, and fewer events. The scene just feels less inspiring and less bustling, but it’s difficult for me to fully gauge because, at the same time, I’ve gone from being a young man to a middle-aged guy who prefers staying home on the couch.

There’s still a lot happening post-pandemic, but it’s a much younger person’s world now. The new movements and trends are coming from places I don’t particularly understand. Instead of feeling alienated by it, I embrace the fact that it’s simply not for me. For instance, I’ll never fully get hyperpop, just like how when I was younger, we all hated nu-metal. That genre was for a different kind of „dork,” and not the cool ones—more like the type associated with negative stereotypes. But young people today are relating to that music in a way that’s different from how I did back then. Rather than criticize it or say that my generation got it right and they’re getting it wrong, I recognize it as just different. I didn’t come of age during COVID, nor did I grow up with social media shaping my mind. I can’t fully grasp how these things have rewired the brains of young adults or what impact they’ve had on the subcultural world, especially in New York, but also everywhere else.

And that’s okay. It’s fine for me to accept that I’m getting older. The only reason I’m still in New York is because my wife has a good job that she can’t easily do elsewhere, and I work from home. If it weren’t for that, we’d probably be living in the middle of nowhere, going on hikes, and I’d be making music in a cabin somewhere. I’m content with where I am in life.

I wanted to ask you about the upcoming record. I have a note from your PR mentioning that it’s a record about a man locked in a lifelong struggle with an eating disorder. Can you elaborate on that?

Yes, it’s funny because even a year ago, I wouldn’t have felt comfortable elaborating on this, and I still don’t feel entirely comfortable now, but I think it’s necessary. I suffer from Bulimia Nervosa, and I’ve had it since I was probably around 12 years old. Sometimes it’s better, and other times it’s a daily, multiple-times-a-day struggle. There are periods when it goes into remission for months or even years, but it’s always there, locked in my mind.

As I’ve gotten older, certain things about my body and self-image have gotten worse. My metabolism has slowed down, and when I look in the mirror, I’ve never seen what I wanted to see—whether I was skeletal, fit, muscular, or anything else. Right now, I’m trying to find a way to live in acceptance of my body and my age. At the end of the day, this is a mental illness. It obviously affects my body and has done terrible things to it. I have ulcers, and I’ve bled from places where you’re not supposed to bleed. But the real struggle is mental, being locked in with an inaccurate portrait of myself. As I get older, I’ve realized that I’ve been playing in bands for a long time, and I’ve played on more records than I can count. There’s no money in it anymore, and I’m not trying to achieve any kind of social headway. I’m not looking for anything other than to feel better because playing music makes me feel better.

With that, I don’t have the time, economic resources, or physical resources to make music about nothing. At this point, it has to be about something substantial, something that directly relates to my life and helps me work past whatever is psychically and spiritually in my way. This eating disorder has been a psychic and spiritual roadblock my entire life. That’s the long-winded, rambling answer to where I’m at right now.

Do you feel like working on this record has helped you?

I’m not sure. I can say that I’ve been in remission for a while now, especially since the press cycle for this record began. It’s been clearer in my mind. I don’t feel the same degree of compulsion that I’ve felt at many other points in my life. For the moment, it feels like it’s not a negative. We’ll see where it ends up, but right now, I can only focus on today, and at this moment, it’s not a negative, which is something.

It’s interesting because, as you mentioned on your substack, this topic is somewhat taboo and not as widely discussed. I started to wonder why that is, and it’s true—it doesn’t have the same „appeal” as topics like depression, which might receive more attention. People don’t talk about it as much, which I find intriguing.

When I was growing up, this was a very gendered issue. There was this belief that men don’t deal with these kinds of compulsions or struggles. It was almost as if men were expected to be immune to such things. I know others have addressed these themes in songs and art, but there isn’t a large body of work about it from a male perspective. And I am very much a man. Part of me feels weird about that, but I can’t imagine it’s any easier for women, non-binary, or trans people. It’s something that haunts all of us, regardless of gender.

You’ve been really open in your art, almost like an open book. It’s something I cherish in artistic expression. But I’m curious—was there a specific point in your life when you decided to be this open? Because being that vulnerable can be also scary.

Yeah, there was a point when that happened, in my late 20s to early 30s. Most of what I write about is based on life experiences, and a lot of those experiences are kind of dark. But I realized that rather than hiding that darkness, facing it head-on made me feel better. It wasn’t about exploiting or capitalizing on it, but more about confronting it honestly. It gave me narrative fuel—my worst times, the things that haunt me, also inspire me.

I could couch all this in metaphor, but I’d rather not, because it feels less personal or rewarding. I don’t really consider myself a musician, even though I compose music. Sometimes, I think of myself as somewhat of a storyteller, but all the stories I have are based on things that have happened. In a lot of the circles I’m in, your darkest moments can be your greatest assets if you let them, as long as you approach them with honesty and kindness and try to work through them instead of wallowing in them. Before that realization, my work was mostly about depression and anger—how angry I was at everything and everyone around me. But in my late 20s, early 30s, I realized that for me, anger and a certain kind of glorified self-loathing were unproductive. That’s when I made the shift.

Uniform’s music releases often come with a specific theme or concept. When you’re writing, do you always start with a concept in mind?

It doesn’t always have to be a concept, but I do like couching my work as a callback to something else. It’s not so much that I’m inspired by these things; it’s more that they’re works I enjoy, and they often have titles I can reappropriate to be about something else as it applies to my life or whatever I’m fascinated by at the moment. To me, they serve as little Easter eggs—some more obvious than others. When people who are into that stuff get it, it leads to another conversation. It’s kind of like, by the dorks for the dorks.

It’s not common to see a musician who also writes about music. There’s a saying that every music journalist is just a failed musician. I guess it’s difficult to apply that sentiment to you!

Yeah, sometimes that saying holds true—there are definitely failed musicians and cultural hacks who do it, and that’s not to say I’m not one of them. But when it comes to writing about music, I try to approach it as, if I can’t do it, I’m not going to talk shit on it. I’m not equipped to talk about a ska band because I hate that shit, but I also can’t make it, so what am I to say?

When I write about music, it’s more from the perspective of a sociologist. I’m fascinated by culture, by underground movements. I write about other things too—literature, true crime, whatever I’m working on. But writing about music, honestly, I kind of fell into it. I was unemployed for a bit and got hired by a major label who had this website they were doing. I was literally writing for a paycheck. I probably wrote a hundred articles about Slipknot, and I’ve never even heard Slipknot.

Are you kidding me?

If you’re my age or older, chances are you haven’t actually heard Slipknot. But if you’re six months younger than me, Slipknot might have been the biggest, most important band in the world to you. For me, writing about music became a trade, like being a plumber or an electrician. It helped me develop a craft, and I can take that craft and apply it to different work, which I’m doing now. But yeah, when it comes to music journalism, I think the approach should be, if you can’t do it, don’t talk shit about it. For me, it’s a gig, a living, and I’m grateful for it.

So, I was curious because you write so well—it’s truly a pleasure to read your work. You must know that you’re a talented writer. When did you first realize that writing was something you excelled at?

I was young. I started writing poetry in middle school. It was one of the few times teachers were happy with me, and it was the only thing I ever got A’s in, that and theology because I was interested in religious topics. But whenever I tried to do it on a bigger scale, I would hit mental blocks. So, it was something I was told I was good at, but I never felt capable of following through. Then, over the years, I got lucky. A few years back, a friend who was an editor for a big music website offered me some money to write. I was trying to transition out of a retail job I’d had for a decade and a half, so I started doing it more.

But honestly, it’s very recent. It’s only within the past two or three years that it’s become a daily habit and something I actually see through to fruition. I feel better when I do it. It takes me a long time to write and to edit, and that can be draining because I feel like I’m dealing with writer’s block perpetually. Even when I’m not, I get frustrated and stop. Having a job where I had to write about stuff I didn’t care about really helped. I learned how to not be so precious with what I was doing and just get it out and fix it in the rewrite. That’s kind of where I’m at now. I write because I love it. It’s hard work for me, much harder than any job I’ve ever had. But it’s also just one of about a thousand jobs I still have. If you’re asking me what I do for a living, the list is long. I’m a band manager, a musician, a writer, and I sell merch for people. Tomorrow, I’m a merch guy for a Red Bull pop-up event for a rap star I’ve never heard of. I work where I can, and I’m grateful that writing is part of my toolkit.

You’re writing a book. Can you say something more about it?

Not just yet. It’s going to be an essay collection, mostly coming from personal experience. There might be some poetry in it. I’m workshopping it all on Substack right now because Substack forces me to have a deadline. I only work with a deadline. If I don’t have one, I don’t get anything done. So, if I have people who are paying for my work—which, surprisingly, seems to be happening—I have a commitment to them to have a certain amount done in a certain amount of time, every week or two. I’m trying to let the book grow out of that. We’ll see what it shapes up to be. We’ll see if it lives anywhere other than Substack. I don’t know if it will, but at the moment, I don’t care. It just feels good to be working.

Many people find it challenging to write about their feelings and personal experiences, especially love. It’s refreshing and touching to see how openly and beautifully you express your love for your wife in your posts.

Trust me, I am underselling her. Words don’t do justice to who she is. There isn’t much I have to give. I’m a working artist, and she’s a highly experienced, intelligent, resourceful, and brilliant music executive. She’s a catch—hilarious, perfect—and I’m just a guy with neck tattoos who barely graduated from high school. At this point, I’m lucky if I pull in 30 grand a year, so I have to give her something.

In your latest Substack post, you mentioned that Lars Ulrich is a great guy. I have to admit, this is one of my favorite topics because „Some Kind of Monster” is my all-time favorite music documentary. In my friend group, there’s a lot of debate about who’s Team Lars and who’s Team James. I’m genuinely surprised to hear that you might be on Team Lars!

It’s very much a partnership between those two. As a recovering alcoholic who lives in a state of pure rage, the way James Hetfield plays guitar, the way he downstrokes—no one has ever done that before, and no one will ever do it again. He’s just a ball of fury and misery that I completely relate to. I don’t relate to Lars at all. That being said, I don’t think James is a genius. He’s just raw. I do think Lars is a genius. Lars is the person who arranges every Metallica song. Those first four records, the arrangements wouldn’t exist without Lars. He put all the songs together. James might have written the riffs, Kirk might have brought the solos, but Lars composed the whole thing. He’s not a great drummer, but he does his job.

You can’t listen to the breakdown in „One” and tell me that the double kick there sucks—it doesn’t. The man has captured lightning in a bottle more times than pretty much any other human being in heavy metal. That’s that. I think he’s a genius. He was right about Napster. He was an asshole about it, but I’ve met a few geniuses in my day, and not a single one of them is a cool person. They’re all profoundly messed up, tortured, miserable, or off the rails in some other way. They’re incredibly self-destructive and wreak havoc wherever they go. I don’t wish genius on my worst enemy. I had to block a genius on Instagram the other day—a miserable piece of work, but still a genius. Lars is a genius. He’s not cool. I don’t want to hang out with Lars. I don’t wish Lars on anyone. But there’s no Metallica without him, and you can’t discount the guy. He deserves more credit than he gets, but he’s also probably more messed up than people realize. I take the good with the bad. I don’t have to hang out with him, thank God.

I really appreciate that moment in the movie when Lars’s father listens to the songs and isn’t very impressed, you can see Lars’s reaction shift back to that of a child seeking approval. It’s a poignant moment that really humanizes him and makes you feel for him. It’s like you can almost see the vulnerable side of him yearning for his father’s pride.

Do you know about Lars’s dad?

Yes, of course.

Coming from that and what Lars was supposed to be, the family moved to the US so Lars could be a tennis star, and he just didn’t. In his mind, he’s a perpetual disappointment. He didn’t do the thing his father and grandfather did, so nothing will ever be good enough. I feel for the guy in that regard. However, I can only feel for a millionaire so much.

It’s good to know you’re not fully on Team Lars after all! A few years back, you discovered that you have some Jewish heritage.

Oh gosh, I’m a quarter Jewish.

I was wondering, did it affect you on any level?

Other than me thinking it’s awesome, not really. Do you know the story of how I found out?

Yes. Your father told you that.

My father was a complicated guy. I loved him very much. He’s the only human being I’ve ever 100% related to. That said, he was a really tortured fucking dude—a drug addict, in and out of remission. He came from a really intense working-class background and worked his way up to the heights of his profession. He was a dentist and did really well, which isn’t easy for a junkie from outside of Boston. We had a hard relationship, but I loved him and related to him deeply. We had the same sense of humor.

When he was 50, he got skin cancer. It went into remission, came back, and eventually turned into pancreatic cancer. When he told me, he took me out to lunch. I was upset, but then he told me “I’ve got some good news”. On top of that: my father was adopted. We knew his biological mother was his living aunt, who raised him. It was some Boston Irish Catholic stuff. We never knew who his father was and assumed it was this Italian guy she had been dating but wasn’t allowed to because Italians and Irish didn’t get along at the time.

Then we found out through his cancer that it exclusively happens to Ashkenazi Jews, which meant his biological father had to be Jewish. It made a lot of sense given the way my family reacted to it. And if you look at my father and you look at me, like, you know, we look somewhat alike, you know? We have the features of Ashkenazi Jews. So when he told me he was just like “You know what the good news is? That means I’m half Jewish, that means you’re a quarter Jewish.” That explains our sense of humor, it explains… I don’t know, it explains everything good about us.

You mentioned that you’re involved with Alcoholics Anonymous. I recently read „Quit Like a Woman” by Holly Whitaker, where she critiques AA, describing it as somewhat misogynistic due to its origins as a program created by men, for men. She argues that it lacks the supportive, nurturing environment she believes is crucial for women, and contrasts it with her own program designed to be more supportive and empathetic. Do you find AA to be a strict program, or do you feel it offers genuine support and compassion?

I see both sides to it. I really do, and I’ve experienced both sides. You know, like, Bill Wilson, the guy who founded Alcoholics Anonymous, was a pretty fucked-up dude. And, you know, his wife Lois founded Al-Anon on the heels of Alcoholics Anonymous, largely because of how fucked-up Bill was and how fucked-up he continued to treat her. There are things in the 164 pages of the book, „Alcoholics Anonymous,” that I find, at this point, to be at best antiquated, at worst misogynistic.

But, you know, I know people who are die-hard, follow the Big Book to the letter, like it’s the instruction manual, and take it very literally—much like evangelical Christians take the Bible very literally. That doesn’t work for me. When I first got sober, and I didn’t have anywhere to go, didn’t have anything to do, I found that this really intense, by-the-book approach gave me something to focus on, and that helped me stay sober. But as time has gone on, it’s become more of a loose garment for me. I’ve been through the steps, and I continue to be involved, though not as much as I used to be. I still stay present in it.*

But I find that rigid thinking tends to push people away. And if our goal is to be a big tent and to help others, we have to be welcoming. You can’t just wag your fucking finger at people, telling them what they have to do and what they cannot do. So, for me, at this point, the program is very much open to interpretation. My understanding of a higher power changes constantly. If you asked me what God is today, it’s different from what it was yesterday and what it will be tomorrow. And that’s fine with me.

The thing I gravitate toward is that whatever my higher power is—whether it’s other people or the universe itself—those things don’t want me to be dishonest, unkind, or miserable. So if I act in service to the well-being of others and try to approach others with love and tolerance, which is right there throughout the literature, and if through doing that, I can help another alcoholic stay sober, and that, in turn, helps me stay sober, then it’s a success. But yeah, I do think AA is fucked up in some ways. I don’t go to many co-ed meetings; I mainly go to men’s meetings. The main reason for that is that in co-ed meetings, I see people—mainly men—showing up, trying to impress people, talking a certain way. It gets my antennas up, and I don’t like it. It’s not that I think everyone in those rooms is doing that, but I’ve seen it happen, and it messes with me.

Also, men, women, non-binary, trans people, gay, queer—everyone has their own life experiences, and we’re all treated differently by society. In men’s meetings, I go somewhere where society has treated most of us similarly, as opposed to co-ed meetings where we speak in general terms, and the men in the room have had different experiences than the women, who have had to develop different survival instincts and coping mechanisms. It’s not that I find that disingenuous, but it doesn’t work as well for me. And that’s not to say I don’t have lots of women friends in AA—I do—but I don’t sponsor women because I can’t relate to their life experiences in the same way, and they can’t relate to mine. But, you know, that’s that.

***